Small molecules in the treatment of COVID-19 | Signal Transduction ...

Those Insisting The Pandemic Was Human-made Are Ignoring The Known Facts

Today, Americans are more likely to believe that the novel coronavirus, which causes Covid, came from a lab rather than from an animal infecting a human, even though most studies overwhelmingly suggest the opposite. For months, proponents of the idea that the novel coronavirus escaped from a lab have been hotly anticipating a declassified U.S. Intelligence report on the origin of the pandemic. Now the report is out… and it was kind of a dud for the "lab leak" theory.

The report found "no indication" that Chinese labs were working with any close progenitors of SARS-CoV-2 or of any "specific research-related incident" occurring inside a lab that could have caused the pandemic.

The report found "no indication" that Chinese labs were working with any close progenitors of SARS-CoV-2 or of any "specific research-related incident" occurring inside a lab that could have caused the pandemic.

And yet "lab leak" advocates are claiming vindication anyway.

How? They point to two recent news reports they say back their claim that Covid came from a lab, rather than from an animal infecting a human in a marketplace.

The Wall Street Journal reported in February that the Department of Energy changed its intelligence assessment to conclude that the novel coronavirus "most likely arose from a laboratory leak." This month, several outlets reported that unnamed intelligence sources claimed that a U.S.-funded scientist researching coronaviruses was among three people working at the Wuhan Institute of Virology who in November 2019 "became sick with an unspecified illness."

But these stories are not the smoking guns lab leak proponents make them out to be.

Let's start with how the scientific evidence for the origin of the novel coronavirus evolved. In March 2020, The Lancet published an open letter from more than two dozen eminent scientists, experts on viruses and epidemiology, that condemned "conspiracy theories suggesting that COVID-19 does not have a natural origin."

That said, one did not have to be a conspiracy theorist to wonder if the virus may have accidentally escaped from a lab. Some leading virologists did wonder about it. In a January 2020 email to Dr. Anthony Fauci about the virus, Kristian Andersen, a virologist from Scripps, said "some of the features (potentially) look engineered" and that he and his colleagues "all find the genome inconsistent with expectations from evolutionary theory."

Then in May 2021, a group of more than a dozen scientists — including evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey — published a peer-reviewed letter in Science calling for more investigations into Covid-19's origin, and maintaining that both a natural origin and an accidental lab leak remained viable theories.

One did not have to be a conspiracy theorist to wonder if the virus may have accidentally escaped from a lab. Some leading virologists did wonder about it.

But here's where it gets interesting. The same scientists who initially found a lab leak scenario plausible — Kristian Anderson and Michael Worobey — reached the opposite conclusion after they studied the virus.

Last summer, Worobey and Anderson co-authored two major peer-reviewed studies looking at the earliest cases of Covid-infected patients in Wuhan, concluding that "the emergence of SARS-CoV-2 occurred through the live wildlife trade in China" and that the wet market that hosted that wildlife trade "was the epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic."

There's been nothing equivalent to those findings in the published literature on the lab leak theory side of the debate. There just hasn't.

As Worobey told The Associated Press for a story published in February, "The scientific literature contains essentially nothing but original research articles that support a natural origin of this virus pandemic."

On the other hand, the lab leak theory is built not on hard evidence, but on circumstantial stuff. It's a theory based wholly on questions, not actual findings.

For example, lab leakers ask, if Covid was natural in origin, why haven't scientists yet discovered the exact animal from which the virus crossed into humans?

Forgive me but, so what that they haven't? As a January article in Slate pointed out, "It took 29 years to definitively identify the source of Ebola, 26 years for HIV/AIDS, and 15 years for SARS." So the lack of an identifiable source, especially this soon, does not suggest a lab leak.

The lab leak theory is built not on hard evidence, but on circumstantial stuff. It's a theory based wholly on questions, not actual findings.

Meanwhile, scientists continue to pile up evidence that points strongly to an animal source. In March, Andersen and Worobey, along with more than a dozen other scientists, analyzed the genetic data from samples taken at the wet market in the early days of the outbreak and in one significant Covid-positive sample found fragments of raccoon dog DNA, exactly the kind of evidence you'd expect to find if animals were the origin of the pandemic.

In fact, the history of pandemics is a history of viruses crossing over from animals to humans, not escaping labs and infecting humans.

That's not to say accidents don't happen at labs. They happen plenty. They just haven't yet, that we know of, resulted in wider outbreaks.

But that leads to another question: Did scientists at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) run the sort of "gain-of-function" experiments that could have "created" something like the novel coronavirus?

Now that is a good question. WIV did apply for a grant to run such experiments in 2018, but was denied. Given China's lack of transparency — which is a big reason we're still arguing about the origin of Covid — it's possible that WIV conducted such experiments in secret. There's no way to know. That's why a June 20 Wall Street Journal report, based on unnamed intelligence sources, that one of the three WIV scientists who fell ill in November 2019 was researching coronaviruses appears to carry such significance.

Never mind that the declassified intelligence report found no evidence "indicating that any WIV genetic engineering work has involved … a backbone virus that is closely-related enough to have been the source of the pandemic." And never mind that the report found these scientists "experienced a range of symptoms consistent with colds or allergies with accompanying symptoms typically not associated with COVID-19, and some of them were confirmed to have been sick with other illnesses unrelated to COVID-19."

Never mind all that. Let's just suppose it happened. Say that scientists accidentally created the novel coronavirus in a lab and these three scientists got infected. You would expect, then, that the earliest cases would have been centered around the Wuhan Institute of Virology and its surrounding neighborhood.

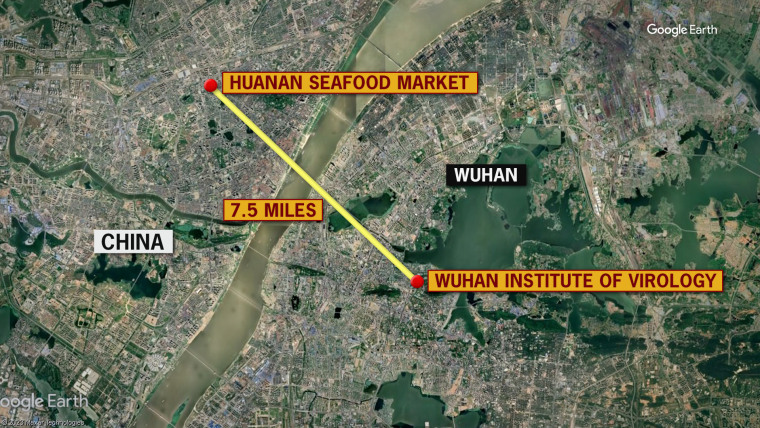

The earliest cases of Covid-19 were concentrated not around the Wuhan Institute of Virology but in a market that's nine miles away by foot.NBC News / Google Earth

The earliest cases of Covid-19 were concentrated not around the Wuhan Institute of Virology but in a market that's nine miles away by foot.NBC News / Google Earth Yet as Worobey's study in "Science" showed, all the earliest cases of Covid-19 were concentrated on the other side of the city, across a river, about seven miles away as the crow flies — nine miles by foot — in the illegal wet market that sold exactly the kinds of animals that led to the outbreak of SARS 20 years ago.

Is it "possible" that Covid leaked from a lab? Sure. But likely? More likely than the wet market?

The entire premise continues to strain credulity, which is why a natural origin remains the best theory in the actual scientific literature.

But what about that Department of Energy's intelligence assessment?

But what about that Department of Energy's intelligence assessment? As CNN reported at the time, three people familiar with the intelligence findings told them, "The Department of Energy's shift was based in part on information about research being conducted at the Chinese Centers for Disease Control in Wuhan, China, which was studying a coronavirus variant around the time of the outbreak."

Excuse me, the "Chinese Centers for Disease Control"?

That is an entirely different lab than the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which lab leak proponents have talked about nonstop since day one.

You can't, as writer Jonathan Katz has said, point to an intel assessment about a totally different lab than the one you've blamed for the outbreak and then claim vindication for your theory!

The declassified intelligence report shed no light on the Department of Energy's sources. But, again, let's just suppose the department got it right. Say that there was a leak from the Chinese CDC in Wuhan, rather than the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

You know what kind of work is not done at that Chinese CDC?

Gain-of-function research!

The Energy Department assessment, if accurate, actually blows up the theory lab leakers have been pushing for three years. Sorry, you don't get to move the goalposts and tell yourself you were right all along.

The Energy Department assessment, if accurate, actually blows up the theory lab leakers have been pushing.

Now, does that mean the lab leak theory is therefore false? No. Of course it remains possible that Covid leaked out of a lab in Wuhan. I am not saying it didn't, nor are the scientists who think it had a natural origin and came out of the wet market. They just want to see hard evidence for the lab leak theory, as do I. We haven't seen any yet, even after the intelligence community released declassified material behind their assessments! If that elusive evidence does emerge, I'll say, "Sure, I was wrong on this, as were most of the scientists I trusted."

But until we see that hard evidence, the burden is on proponents of the "lab leak" theory to disprove what remains the most overwhelmingly likely explanation of a natural origin.

Frankly, they haven't come close.

Updated with new developments, this op-ed is an adaptation of a segment of The Mehdi Hasan Show on Peacock that originally aired March 8.

Human Gene Identified That Prevents Most Bird Flu Viruses Moving To People

Scientists have discovered that a gene present in humans is preventing most avian flu viruses moving from birds to people. The gene is present in all humans and can be found in the lungs and upper respiratory tract, where flu viruses replicate. It was already known to scientists, but the gene's antiviral abilities are a new discovery.

A six-year investigative study led by the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research found that the BTN3A3 gene is a powerful barrier against most avian flu viruses.

Although relatively rare, some avian flu virus strains have periodically spilled over into humans. Two of the most recent H5N1 cases were reported in UK poultry farm workers in May this year. Human cases of H5N1 bird flu were first found in Hong Kong in 1997. Globally since 2003, 873 human H5N1 infections have been reported to the World Health Organization. Of those, 458 people died.

The study found that some bird and swine flu viruses have a genetic mutation that allows them to escape the blocking effects of the BTN3A3 gene and infect people. By tracking the history of human influenza pandemics and linking resistance to the gene with key virus types, the researchers concluded that all human influenza pandemics, including the 1918 Spanish flu and the 2009 swine flu pandemics, were a result of BTN3A3-resistant strains.

The findings suggest that resistance to the gene could help determine whether flu strains have human pandemic potential or not. That may lead to testing of wild birds, poultry and other animals susceptible to flu viruses such as pigs, for BTN3A3-resistant viruses.

"The antiviral functions of the [BTN3A3] gene appeared 40m years ago in primates," said Prof Massimo Palmarini who led the study and is director of Glasgow's virology research centre. "Understanding the barriers that block avian flu in humans means better targeted solutions and better control measures to prevent the spillovers.

He said that if a gene-resistant virus was identified, "we can direct preventative measures to those viruses, sooner, to prevent the spillover [into humans]".

Dr Rute Maria Pinto, the study's lead author, said: "It's pretty amazing, isn't it? We are all fairly proud about the outcome. This gene had been identified before, and other functions were attributed to it, but we found that the gene is antiviral against avian flu. No one had found that before."

She said the discovery was expected to have immediate practical applications. "Now, when we find cases of bird flu, we can basically swab sick birds, carcasses or faeces and find out whether the virus can overcome the BTN3A3 gene, simply by looking at its sequence and determining if this virus is more or less likely to jump into humans. If the virus can in fact overcome BTN3A3 then stricter measurements should be put in place to prevent spillovers."

Bird flu: H5N1 virus in Brazil wild birds prompts animal health emergency

Read more

Pinto added: "As a scientist we are expected to find solutions to problems, to give back to the taxpayers that fund this [research], and to find something that can be used straight away is really impactful."

The study was also able to retrospectively identify increases in gene-resistant viruses ahead of previous human spillovers.

Before the H7N9 bird flu virus outbreak, which first infected humans in China in 2013, the study found "an increased frequency of the BTN3A3-resistant genotype [in birds] in 2011-2012". To date there have been almost 1,570 cases of H7N9 and at least 616 deaths.

"I guess what these observations provide is a snapshot of what the frequency of the BTN3A3 resistant gene was at different period of times in the birds," Palmarini said. "Because birds haven't got BTN3A3, there is no evolutionary pressure to keep, or not, those traits."

He said certain mutations "might make the virus more or less fitter in the birds" but this had not yet been studied.

Similarly, before the 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic, the study found H1N1 gene resistance in pigs occurring between 2002 and 2006. The swine flu pandemic is estimated to have killed between 150,000 and 575,400 people during the first year the virus circulated in humans.

Human Gene Blocks Avian Flu Virus In Remarkable New Discovery

Scientists have identified a human gene that acts as a powerful barrier against most avian flu viruses.

As The Guardian reports, the gene known as BTN3A3 has been found to prevent the transmission of these viruses from birds to humans.

This remarkable finding sheds light on the potential for preventing future avian flu pandemics and provides new insights into the genetic factors influencing virus transmission.

Human Gene Can Fight Off Avian FluThe study, led by the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, involved a six-year investigation into avian influenza viruses (IAVs).

Researchers discovered that the BTN3A3 gene, present in all humans, possesses strong antiviral properties against avian flu. This gene is primarily found in the lungs and upper respiratory tract, where flu viruses replicate.

Previously known to scientists, the gene's ability to block avian flu viruses represents a significant breakthrough.

By inhibiting the replication of viral RNA at the early stages of infection, BTN3A3 effectively prevents avian influenza viruses from spreading in mammals like humans.

Read Also: AI Tool Shows Promising Results in Identifying Sperm for Severely Infertile Men

Interestingly, the scientists also found that all previous human influenza pandemics, including the devastating 1918 Spanish flu and the 2009 swine flu outbreaks, resulted from BTN3A3-resistant strains.

What the Discovery Means for HumansThe implications of this discovery are far-reaching. By understanding the genetic factors that enable avian flu viruses to cross the species barrier, scientists can better assess the risk of potential pandemics.

The study revealed that particular bird and swine flu viruses possess genetic mutations that allow them to evade the blocking effects of BTN3A3, enabling them to infect humans.

Researchers have also linked resistance to the BTN3A3 gene with key virus types by tracing the history of human influenza pandemics.

Predicting the FluThis finding suggests that monitoring the presence of BTN3A3-resistant viruses in wild birds, poultry, and other susceptible animals could help identify potential human pandemic strains.

The ability to identify gene-resistant viruses quickly offers practical applications. By analyzing the genetic sequence of avian flu viruses, scientists can determine whether the virus is more or less likely to jump into humans.

This information can aid in implementing targeted control measures to prevent spillovers and improve public health responses.

The World Health Organization (WHO) issued a warning in February about the likelihood of Bird Flu spreading to people after H5N1 influenza recently began spreading to other mammals.

According to WHO, the risk of transmission to people remains minimal.

What's In the NewsThe discovery of the BTN3A3 gene's potent antiviral abilities against avian flu viruses marks a significant milestone in our understanding of virus transmission.

This groundbreaking study provides insights into the mechanisms that prevent avian flu viruses from spreading in humans and highlights the importance of genetic factors in assessing pandemic risks.

Stay posted here at Tech Times.

Related Article: Avian Flu Endemic in Wild Birds Signals Year-Round Threat to Food Supply, Say Experts

ⓒ 2023 TECHTIMES.Com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.

Tags:

Comments

Post a Comment