What are Flu Antiviral Drugs | CDC

Guinea Ebola Outbreak: Orphans Share Their Stories, Ten Years On

This year marks a decade since the largest ever outbreak of Ebola began, which killed more than 11,000 people in West Africa.

The three main countries affected were Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Guinea, where the outbreak started. It left around 20,000 children without one or both of their parents.

Two teenagers, in western Guinea, discuss how they managed to cope with the loss of their parents at such a young age and the stigma within their community at the time.

Produced and Edited by Soraya Ali

Joel Breman, Who Helped Stop An Ebola Outbreak In Africa, Dies At 87

Dr. Joel Breman, a specialist in infectious diseases who was a member of the original team that helped combat the Ebola virus in 1976, died on April 6 at his home in Chevy Chase, Md. He was 87.

His death was confirmed by his son, Matthew, who said his father died of complications from kidney cancer.

"We were scared out of our wits," Dr. Breman, recollecting his pioneer mission, told a National Institutes of Health newsletter in 2014, as a new and even deadlier Ebola outbreak raged that year.

Nearly 40 years earlier, his team of five had just landed in the interior of what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo, at a remote Roman Catholic mission hospital. They were up against a viral infection that had no name, whose origin was unknown, and that was accompanied by high fever and bleeding that led to a painful and quick death.

Dr. Breman, dispatched by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, had only what he described to the N.I.H. As "the most basic protective equipment" against the disease, in contrast to the full-body spacesuit-like gear that was standard in the later outbreak. He and others on the team, laboring in intense heat and bitten by sand flies, "developed rashes and didn't know if we would catch the virus too," he said.

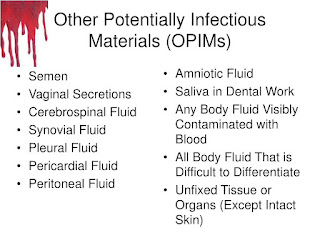

But he calmly began deploying the techniques he had honed on earlier missions to Africa, on anti-smallpox initiatives in Guinea and Burkina Faso. He interviewed patients and witnesses, traveling from village to village and going from house to house. He and his colleagues, he recalled, soon determined that the infection was "spread by close contact with infected body fluids," and that it had been propagated at a rural hospital that was using unsterilized needles.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.

Battling The Ebola Outbreak In DR Congo

Health workers in the Democratic Republic of the Congo have been battling an Ebola outbreak for over a year. More than 2,100 people have died, and the World Health Organization has declared it a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. People on the frontlines say there are signs of progress, but there's more to do, and they need international support.

Dr. Mory Keita is a WHO Field Coordinator in the city of Beni in North Kivu, right in the heart of the Ebola epidemic. He has spent months on the ground responding to the outbreak, and he says things are improving thanks to vaccinations, earlier detection and better coordination between local and international responders in DR Congo.

Click to hear from Ebola responder Dr. Mory Keita, WHO Field Coordinator in Beni, DRC.The WHO's latest update says there were 57 new confirmed cases in the week to September 17 in the provinces of North Kivu and Ituri. It's a minor increase from the previous week, which -- at 40 -- had seen the lowest figure in six months.

But the organization warns that there is no way to be sure the good news will continue. It is still a challenge to trace the movement of people from Ebola zones to other areas where the situation is under control. New hotspots are emerging, and the WHO says the national and regional risk levels remain very high.

The fight against Ebola at a crossroadsCountries in Africa have been battling Ebola on and off for 40 years.

In the early stages of the current outbreak, health experts flew in from many countries to try to ensure there was no repeat of the outbreak that ravaged West Africa between 2014 and 2016. The disease killed more than 11,000 people in that period.

Last month, scientists said they had found two drugs that appeared to be effective in patients with early symptoms. The drugs are still undergoing clinical tests, but the news raised hope that there may one day be a cure. Vaccines have also become more readily available in the country. They are not commercially licensed, but health officials say they offer a high degree of protection.

Insecurity and mistrust hampering progressBut not many experts are forecasting a rosy road ahead. The WHO's regional head, Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, says their work is being hindered by suspicion and mistrust of outsiders in a country that suffered decades of conflict. She says international experts and even health officials from within the country are considered outsiders.

The WHO says there have been more than 200 violent attacks against healthcare workers this year, some of them fatal. A doctor deployed by the WHO was killed in April in an attack on a hospital in Butembo, North Kivu.In addition, community violence in Lwemba in Ituri Province has led to the suspension of all response activities until further notice.

More than 100 armed groups are active in the Ebola hotspots, which are also mineral-rich areas. Tensions over land and resources remain high there. Health officials say some people who are poorly informed about the disease mistakenly view Ebola response centers as "death traps."

Ebola treatment center set on fire in Butembo, DRC in February. Community commitment leads to Ebola resilience

Ebola treatment center set on fire in Butembo, DRC in February. Community commitment leads to Ebola resilience Despite the security problems, Dr. Keita says he and his team are staying, and are determined to stop the outbreak by the end of the year. "Our mission is to stay and deliver," he says. "We have to finish the job."

He says the key will be getting a commitment from local community members. The WHO is trying to involve youth associations, women's groups and religious organizations -- community groups that have already built up strong trust.

Local students visit an Ebola treatment center in Beni. International support has to continue

Local students visit an Ebola treatment center in Beni. International support has to continue The Japanese government has sent an emergency response team to cooperate closely with locals.

Dr. Masahiko Hachiya was part of the team. He is an expert on infectious diseases and has just returned from Kisangani, a city that hosts an international airport. The city requires higher levels of quarantine and surveillance to ensure travelers don't bring the virus in.

Dr. Hachiya says the response team spent a lot of their time building trust with local people, and teaching health officials the basics of disease prevention and control.

A lesson in how to put on a hazmat suit.

A lesson in how to put on a hazmat suit. Dr. Hachiya says he was surprised to discover that even healthcare workers didn't know how to secure clean water. Some had no knowledge of hazmat suits, others didn't know how to put them on and take them off.

The United States, the UK and other countries have been offering help, spending millions of dollars on training for healthcare workers and helping communities understand the disease.

Ebola can only be truly eradicated with continuous support from the international community and a lot more local understanding.

Comments

Post a Comment